CCUS AS WE KNOW IT!!!

CCS technology is essential for capturing CO₂ emissions, mitigating climate change, and supporting sustainable environmental solutions.

Abha Sharma

5/23/20258 min read

Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) is one of the most promising technologies for addressing climate change by reducing the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the atmosphere. As one of the major greenhouse gases contributing to global warming, CO₂ levels in the atmosphere have risen dramatically since the industrial revolution. The Earth’s atmosphere now holds approximately 3 trillion metric tons of CO₂, and concentrations are climbing by roughly 40 billion tons annually due to human activity, particularly fossil fuel combustion. By 2024, the atmospheric concentration of CO₂ has reached over 420 parts per million (ppm), which is well beyond the 350 ppm threshold considered safe for a stable climate. To stabilize the climate and limit global warming to 1.5°C or 2°C, it is estimated that humanity needs to remove 10–20 gigatons (Gt) of CO₂ per year by 2050. The deployment of CCS technologies could play an essential role in this global effort. However, beyond mere sequestration, utilizing captured CO₂ in productive ways offers an additional dimension to CCS that may further accelerate its deployment and economic viability.

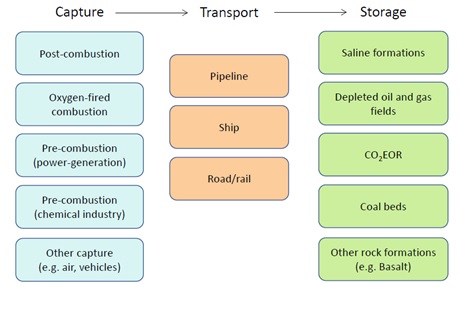

CCS refers to the process of capturing CO₂ emissions from industrial processes, particularly from power plants and factories, then transporting the captured CO₂ to storage locations, typically deep underground, where it can be stored for centuries. CCS technologies also include Direct Air Capture (DAC), which directly extracts CO₂ from ambient air. While CCS is not a silver bullet for climate change, it is considered a crucial complement to renewable energy, efficiency improvements, and other climate solutions. The utilization of captured CO₂, part of an emerging field known as Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS), presents a novel opportunity to offset the costs of sequestration while helping to mitigate climate change.

Historically, CCS has its roots in the oil and gas sector, specifically in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) projects. As early as the 1970s, CO₂ was injected into oil fields to increase oil production. However, the significant push for CCS as a climate solution began in the late 20th century, particularly with the advent of large-scale projects. The first notable CCS project was the Sleipner Project in Norway, which began in 1996. Operated by Equinor (formerly Statoil), Sleipner was the first large-scale implementation of CO₂ storage, where CO₂ extracted from natural gas was injected into deep saline aquifers under the North Sea. The project has captured and stored approximately 1 million tons of CO₂ annually since its inception. This success showed that CCS could be implemented safely and effectively at scale.

The potential for using captured CO₂ beyond storage has opened new possibilities, especially in industries and sectors where emissions are hard to eliminate, such as cement, steel, and chemical manufacturing. One of the most well-known utilizations of CO₂ is for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR), where CO₂ is injected into mature oil fields to increase oil production. This approach not only helps to extract more oil but also sequesters CO₂ underground, effectively serving a dual purpose. It is estimated that about 70% of global CO₂ utilization is in EOR, amounting to roughly 60 million metric tons of CO₂ annually in the United States alone.

Other forms of CO₂ utilization include converting CO₂ into valuable chemicals and materials. For example, CO₂ can be transformed into synthetic fuels such as methanol or ethanol, which can then be used for transportation or energy generation. Companies such as Carbon Clean Solutions and Carbon Engineering are developing technologies that capture CO₂ from industrial emissions and use it to create a range of products, from biofuels to plastics. This integration of CO₂ utilization into CCS technologies offers an economic pathway to reduce the financial burden of sequestration by creating marketable goods from captured CO₂. A recent study by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimated that the global market for CO₂-derived chemicals could exceed $1 billion by 2026.

Another promising area for CO₂ utilization lies in the construction industry, particularly in the production of concrete. Concrete is responsible for about 8% of global CO₂ emissions, making it one of the largest industrial sources of carbon emissions. Several companies, such as CarbonCure Technologies, are working on technologies that use CO₂ to enhance the strength of concrete while simultaneously reducing its carbon footprint. In these systems, captured CO₂ is injected into the concrete mix, where it mineralizes and becomes a stable carbonate. By using CO₂ to produce more sustainable concrete, the construction industry could significantly reduce its emissions, which would have a major impact on global CO₂ reductions.

The use of CO₂ in algae cultivation represents another innovative method of utilization. Algae are highly efficient at photosynthesizing CO₂ and can be used to produce biofuels, food, and animal feed. By utilizing CO₂ in algae farming, the captured carbon is reintroduced into the economy in a renewable form, contributing to a circular carbon economy. Several projects are underway to scale up algae-based CO₂ utilization, with some estimates suggesting that algae could be used to produce up to 1 Gt of biofuels per year by 2050.

As of 2024, the global landscape for CCS has evolved significantly. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), there are now more than 50 large-scale CCS facilities in operation worldwide, with a collective capacity to capture over 40 million tons of CO₂ annually. This includes projects like the Boundary Dam power plant in Canada, which captures up to 1 million tons of CO₂ per year, and the Petra Nova project in Texas, which captures around 1.6 million tons annually from a coal-fired power plant. Despite these milestones, the total amount of CO₂ captured globally still represents only a small fraction of what is needed to meet climate goals. The IEA estimates that to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, the world must capture and store at least 7–8 Gt of CO₂ annually by 2030, increasing to about 10 Gt per year by mid-century. However, current capacity is far below this target, and achieving these levels requires scaling up efforts substantially.

One of the key challenges facing CCS is the economic viability of such projects. The costs associated with capturing, transporting, and storing CO₂ are significant, and the commercial incentives are often limited. In the case of power plants, CCS retrofitting can increase the cost of energy by 30% or more, depending on the technology and scale. The costs for DAC projects are even higher, with estimates ranging from $100 to $600 per ton of CO₂ captured, depending on the technology used. The need for high capital investment is a significant barrier to the widespread deployment of CCS. As of now, the vast majority of CCS projects are funded through public-private partnerships, with governments playing a key role in providing subsidies and tax incentives to help offset the high initial costs. For instance, the U.S. government has offered tax credits through the 45Q tax incentive, which provides up to $50 per ton of CO₂ captured and stored, incentivizing private investment in CCS projects.

The financial viability of CCS is also influenced by the value of carbon credits and carbon pricing. As global markets for carbon trading and carbon taxes evolve, the price of carbon credits has a direct impact on the economic feasibility of CCS. If the price of carbon credits rises significantly in the coming decades, CCS technologies could become more attractive, providing financial incentives for industries to invest in capturing and storing CO₂. However, the current carbon price is often too low to make CCS economically viable without government support. To provide a clearer picture of the current financial landscape, the IEA estimates that the cost of capturing and storing CO₂ is typically between $50 and $100 per ton, depending on the location and type of project. For many projects, these costs can be offset by selling the CO₂ for use in EOR operations, where the captured CO₂ is injected into oil fields to enhance production. This can provide an additional revenue stream for CCS projects, making them more financially viable.

Another key factor influencing the success of CCS is public and political support. While CCS is widely recognized as an important climate solution, it faces opposition from certain environmental groups and communities. Critics argue that CCS is an expensive and unproven technology that could divert resources away from more sustainable solutions like renewable energy. Others argue that CCS may be used as a justification for continued reliance on fossil fuels, undermining efforts to transition to a low-carbon economy. Despite these concerns, governments around the world are increasingly recognizing the role of CCS in achieving climate goals, and policies are being developed to support its implementation.

As of 2024, several high-profile CCS projects are in the planning or construction stages, highlighting the growing interest in scaling up this technology. In the United States, the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Carbon Capture Demonstration Program has provided funding for several projects aimed at advancing CCS technologies. One of the most notable projects under development is the Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) Illinois Industrial CCS Project, which is expected to capture up to 1 million tons of CO₂ annually from an ethanol production facility. Similarly, the NET Power Project in Texas, which uses natural gas with CCS, is expected to capture up to 1.2 million tons of CO₂ per year. These projects represent a step forward in proving the feasibility of CCS technologies and demonstrating their potential for large-scale deployment.

Internationally, several countries are ramping up their efforts to implement CCS as part of their climate strategies. In Norway, the Northern Lights Project is an ambitious CCS initiative aimed at storing up to 5 million tons of CO₂ annually beneath the North Sea. This project is part of Norway’s larger climate strategy, which includes several initiatives to reduce the country’s emissions and develop sustainable solutions for CO₂ storage. Similarly, the United Kingdom has developed the Carbon Capture, Usage, and Storage (CCUS) roadmap, which aims to develop several CCS hubs across the country by 2030, capturing a total of 10 million tons of CO₂ annually. The UK's goal is to create a carbon-neutral economy by 2050, and CCS is seen as an integral part of this vision. Other countries, including China, Japan, and Canada, are also investing heavily in CCS technology and infrastructure, recognizing its role in decarbonizing industries that are difficult to electrify, such as cement, steel, and chemical manufacturing.

Despite the progress, the road ahead for CCS is not without its challenges. One of the most significant barriers is the availability of suitable storage sites. While there are large areas of the world that are geologically suitable for CO₂ storage, finding and securing these sites is a complex process that requires extensive geological surveys and regulatory approvals. In addition, the capacity to store CO₂ is not unlimited, and some experts have raised concerns about the long-term sustainability of storing large quantities of CO₂ underground. Moreover, environmental risks, such as the potential for CO₂ leakage, must be carefully managed to ensure the safety and effectiveness of CCS projects.

Looking to the future, Direct Air Capture (DAC) is expected to become an increasingly important component of global CCS efforts. Unlike traditional CCS, which captures CO₂ from point sources like power plants and industrial facilities, DAC technologies capture CO₂ directly from ambient air. Although DAC is still in the early stages of commercialization, several companies, including Climeworks and Carbon Engineering, are developing technologies that could scale up the capture of atmospheric CO₂ to significant levels. According to some estimates, DAC technologies could capture anywhere from 1 to 5 Gt of CO₂ annually by mid-century, depending on technological advancements and investment in infrastructure. However, the cost of DAC is currently much higher than traditional CCS, with estimates ranging from $100 to $600 per ton of CO₂ captured. The high costs associated with DAC are one of the main reasons why large-scale deployment has not yet occurred. Nonetheless, if the price of DAC technologies comes down over the next few decades, they could become a vital tool for removing excess CO₂ from the atmosphere and addressing historical emissions.

The global capacity for CO₂ storage is another critical factor in the scalability of CCS. The IEA estimates that the world has the potential to store more than 1,000 Gt of CO₂ in geological formations, far exceeding the amount of CO₂ we are likely to emit in the foreseeable future. However, the deployment of CCS will require significant investment in infrastructure, including pipelines for transporting CO₂ to storage sites, monitoring technologies to ensure the safety and effectiveness of storage, and regulatory frameworks to govern the use of geological storage. According to some estimates, the global investment needed to build the infrastructure for CCS could exceed $4 trillion by 2050.

In conclusion, Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) represents a crucial technology for mitigating climate change by removing CO₂ from the atmosphere. While significant progress has been made in developing and deploying CCS technologies, much work remains to be done to scale up capacity to the levels required to meet global climate goals. The financial viability of CCS is a major challenge, and continued government support, technological innovation, and private investment are necessary to accelerate the deployment of this critical technology. Despite the challenges, CCS has the potential to play a key role in reducing global CO₂ emissions and ensuring a sustainable future for the planet.